Cleveland’s Cory United Methodist was born a Jewish synagogue and community center. Then, it evolved into a Christian church and became one of the nation’s most noteworthy centers of civil rights activism. Now, led by a passionate young pastor, the landmark that hosted crusaders from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Malcolm X is fighting not for equality but for its life.

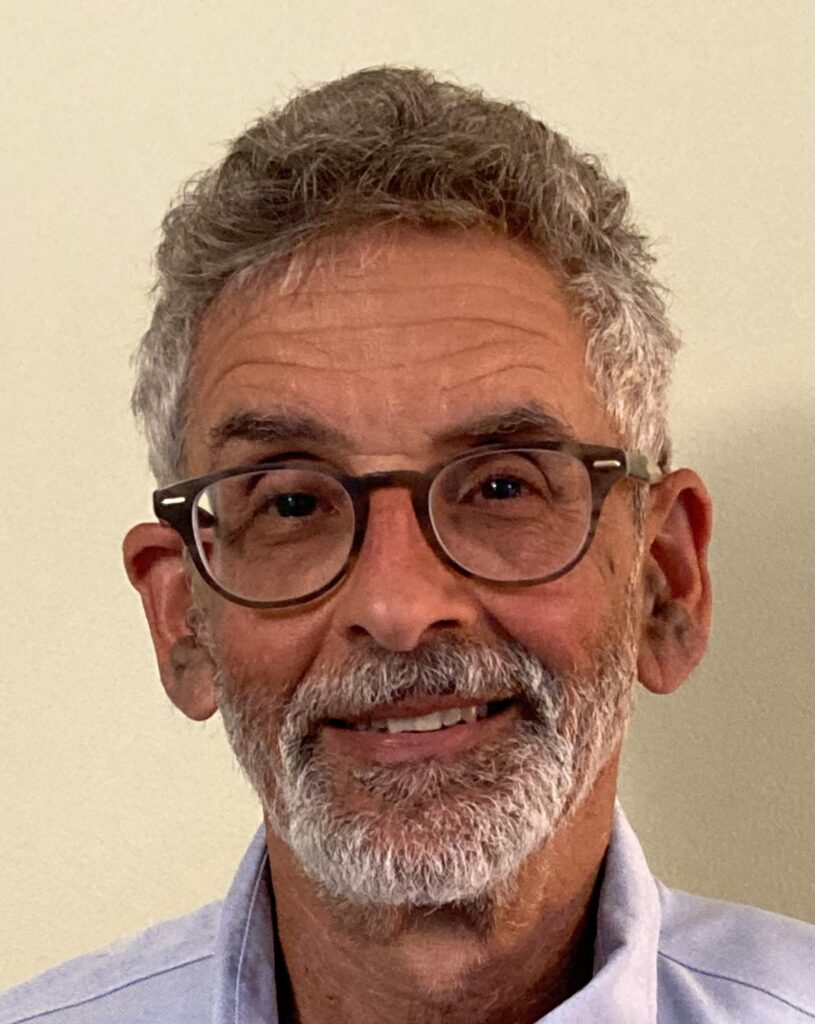

Story by Joe Blundo

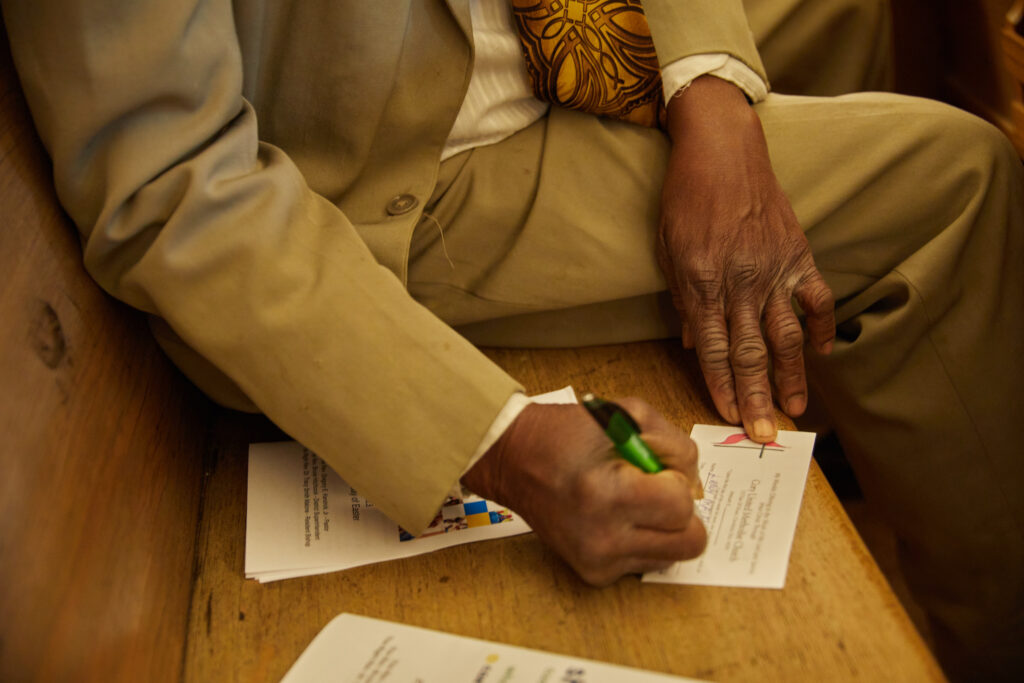

Photos by De’Shaunae Marisa

Rev. Gregory Kendrick Jr. was 12 years old when he preached his first sermon on a neighbor’s front porch.

He grew up on Chicago’s West Side in a neighborhood with gangs and gunfire but also guardians, sanctuaries, places of grace. The Pleasant Ridge Missionary Baptist Church—where Kendrick learned how to pray, how to dance and how to distinguish a salad fork from a dinner fork—was steps away from his home. And a neighbor, Rev. Janey Rucker, held a Bible study on her small, enclosed front porch once a week for kids who were interested.

“We went there for the snacks, and in the midst of getting snacks, we were able to grow and understand what love really meant,” Kendrick said. “It was almost as if we were in this sacred, holy place.”

It was the first place where Kendrick preached—where he publicly proclaimed his faith—although he can’t remember what he said.

“I’m sure it wasn’t good,” he joked, and then reconsidered. “No, I’m sure it was good for its time and its place. I was 12.”

Two decades later, on Cleveland’s East Side, Kendrick, 35, is the pastor of a church in a neighborhood not unlike the one where he grew up. Like Kendrick’s childhood church, Cory United Methodist Church in the Glenville neighborhood of Cleveland is a place where kids learned to pray and dance. It’s also a place where civil rights history was made.

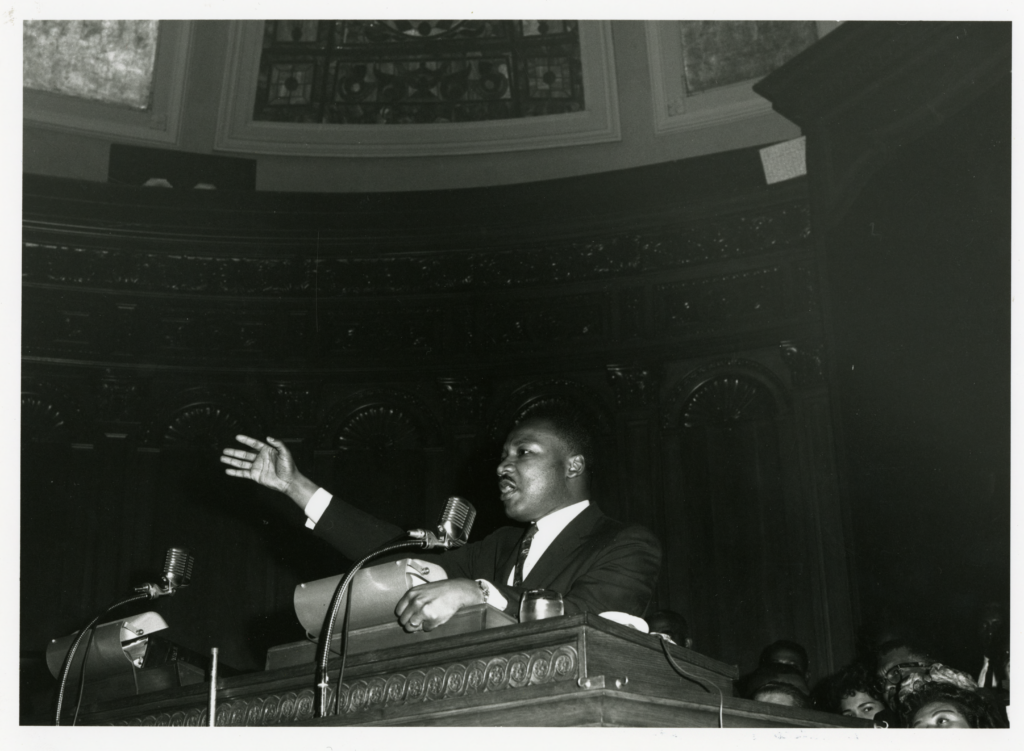

Just days after being released from the Birmingham Jail, for example, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Cleveland to address an overflow crowd at Cory. “We will meet physical force,” he said to thousands, “with soul force.”

Less than a year later, it was from Cory’s pulpit that Malcolm X first delivered his The Ballot or the Bullet speech, often found on lists of the most noteworthy addresses of the 20th century.

“This place is worth cherishing. This place still has value to offer to the world.”

Rev. Gregory Kendrick Jr., Cory pastor

It’s no coincidence that both civil rights leaders came to Cleveland at important moments in the struggle for equality. The city was a center of civil rights activism in the North. And, in coming to Cory in particular, King and Malcolm X were following in the footsteps of W.E.B. Du Bois and Thurgood Marshall, who also spoke at the church.

“During the 1950s and ‘60s it was the site for civil rights activities,” said Margaret Lann, director of preservation services and publications for the Cleveland Restoration Society, which works to ensure the preservation of significant buildings.

Once one of Cleveland’s largest African-American churches, Cory, so dedicated to the civil rights struggle, is now in a struggle of its own. Its aging membership has dwindled to about 150—and only a fraction of them show up each Sunday. Funding is a struggle. And the coronavirus pandemic shuttered most of the social programs for which it was well-known.

But even as churches close at an alarming rate nationwide, there are reasons to hope that this church—whose walls have echoed with so much history—will endure.

Two years ago, it was the first site named to Cleveland’s African American Civil Rights Trail, a collection of important locations in the fight for equality. Cory has also attracted a few grants to preserve its distinctive building. And, perhaps above all, it has Gregory Kendrick, Jr.

Synagogues and Superman

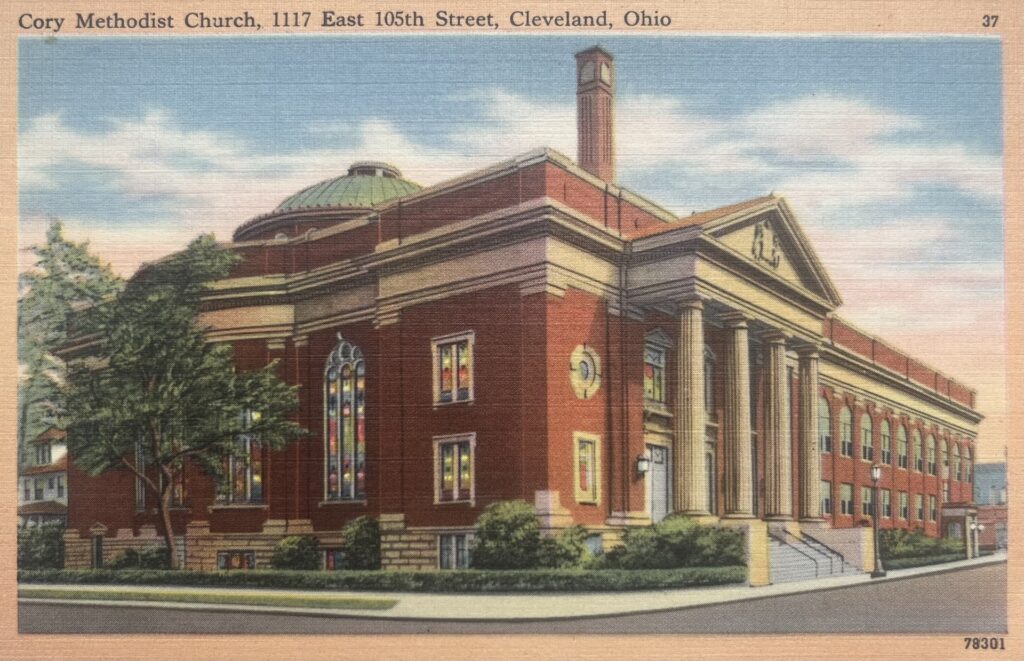

Cory stretches the length of an entire block on E. 105th Street in Glenville, a predominantly Black neighborhood on Cleveland’s East Side.

Glenville was founded as an independent village in 1870. It was known for its farms, its horse-racing track and, on its northern edge, its opulent summer residences near Lake Erie. It grew quickly and developed into a thriving, middle-class Jewish community often called the Gold Coast, with 105th Street the thriving heart of a bustling commercial strip.

One of its claims to fame: In the 1930s, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, both Glenville High School students and the sons of Jewish immigrants, dreamed up a comic strip hero called Superman. Siegel’s home, on the National Register of Historic Places, still stands on Kimberly Avenue.

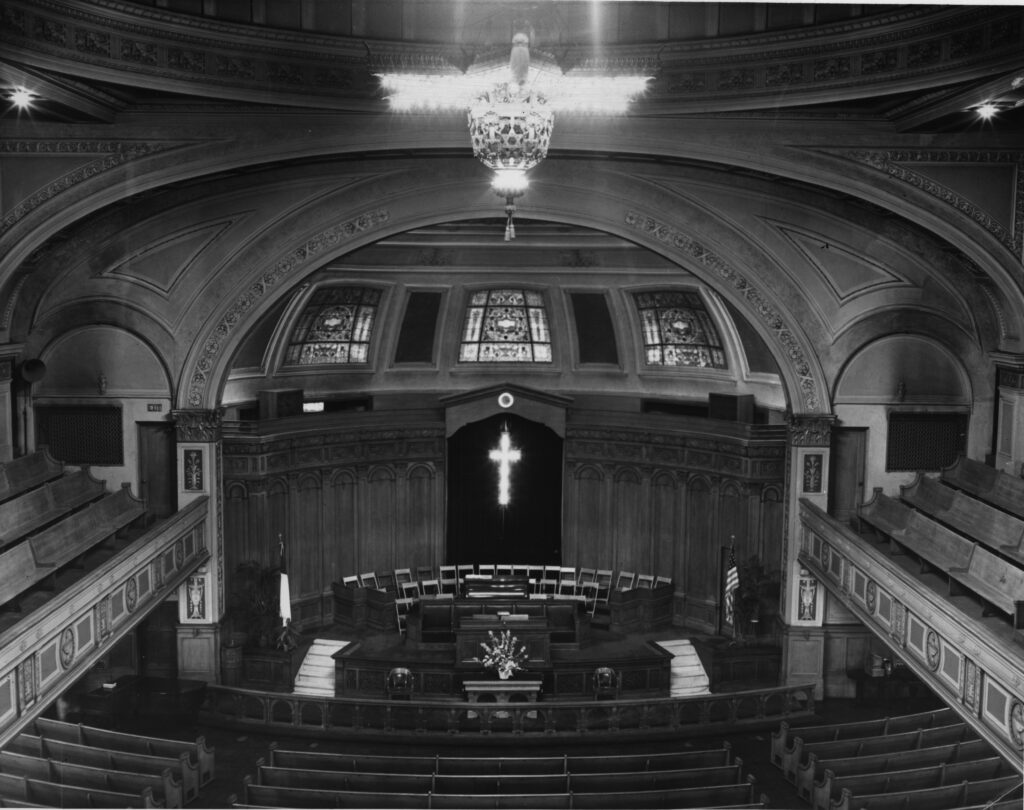

The building now known as Cory was originally constructed as a synagogue and community center by the Jewish congregation Anshe Emeth Beth Tefilo, which moved into the facility in 1921 and renamed itself the Cleveland Jewish Center. Such combination synagogues and community centers were something of a trend at the time, as congregations looked for ways to attract and retain members and to provide recreational and social opportunities that were often denied Jews elsewhere due to discriminatory practices.

The structure was called the largest Jewish center west of the Allegheny Mountains. It’s fluted columns, supporting a pediment with Hebrew inscriptions, loom over 105th Street. The names of Old Testament prophets are carved into the cornices of the building. The synagogue was built with elegant stained-glass windows, seating for 2,400 people, a large ballroom, a gymnasium and a swimming pool. It was one of many synagogues in Glenville at the time.

Then, in 1946, the Cleveland Jewish Center congregation followed its members to the suburbs. The building was sold to the Cory congregation, which moved to Glenville from a site closer to the center of Cleveland.

In the late 1940s, after the second world war, many African Americans migrated from the South to the North. Black citizens came seeking better opportunities and less-oppressive social conditions. It dramatically shifted the demographics of Cleveland neighborhoods.

“The transformation of Glenville was very quick,” Lann said.

In 1940, African Americans constituted about 2 percent of the neighborhood. By 1950, the Black population had reached 50 percent and continued to grow rapidly through the decade. Now, it stands at more than 90 percent.

Housing discrimination restricted most Black families to living on the East Side. Glenville quickly became overcrowded, with many of its large houses converted into rental units. Multiple families sometimes shared space, crowding together so they could afford shelter.

Increasingly weighed down by problems of poverty, crime, blight and racism, Glenville was convulsed by violence in July 1968. A gun battle between Cleveland police officers and Black nationalists, dubbed the Glenville Shootout, killed three officers, three nationalists and one civilian and wounded others. Several days of rioting followed.

Efforts to improve the neighborhood have had limited success. While the southern part of Glenville has been attracting new investment and has higher home ownership rates, the northern section, where Cory is located, continues to struggle.

“It’s a real neighborhood. There’s a community. People look out for each other.”

India Pierce Lee, Glenville resident

More than 60 percent of Glenville’s population lives in or near poverty, according to research by the Center for Community Solutions in Cleveland. The neighborhood also has higher infant mortality rates and higher unemployment than other parts of the city. Glenville’s population fell from 27,000 in 2010 to 21,000 in 2020, according to Census data.

Cleveland City Councilman Kevin Conwell, whose district includes much of Glenville, said major infrastructure improvements and a business-incubator program are among recent efforts to improve the neighborhood. But change, he said, will take time.

India Pierce Lee, executive vice president and chief strategy officer at Cuyahoga Community College, swam in the Cory pool as a child and has lived in Glenville much of her life. She acknowledges Glenville’s problems but fiercely defends it. “It’s a real neighborhood,” she said. “There’s a community. People look out for each other.”

Although it’s technically illegal for lenders to let racial considerations influence their decisions, redlining still happens in Glenville, she said. People with great credit scores have trouble securing mortgages. It’s one of the factors holding the community down.

“But we’re committed to staying in this community as long as God allows,” Pierce Lee said. “As far as I know, I’m going to stay here until they carry me out.”

Gregory Kendrick’s father drove trucks, and his mother did clerical work—a fortunate working-class family in a neighborhood with a high poverty rate. His parents expected Kendrick to excel at school and attend college.

Kendrick discovered Denison University—a small, private college in Granville, Ohio—through the Posse Foundation. It’s a non-profit organization that identifies promising students from the same area and awards them scholarships to attend a college as a group. They find diverse young leaders like Kendrick who might be missed by traditional admissions criteria.

In 2006, Kendrick, arrived at Denison with his best friend Joseph and eight other Chicagoans. They were met with warm welcomes—and the occasional racial slur.

The campus was beautiful, and most people were kind and accommodating, Kendrick said. Yet there were pockets of hostility. “It smells like (racial slur) in here,” someone once yelled when his best friend walked by. There was also a fraternity Halloween party with blackface, noose symbols thoughtlessly employed for humor, the casual use of slurs.

Back home, Kendrick’s half-sister was shot and killed by an assailant who apparently mistook her for someone else.

His faith and his friends sustained him through it all.

“The community of faith in some ways was tangible evidence of God’s presence,” he said. “In the end, my experience at Denison was the most transformative experience of my life.”

Alabama North

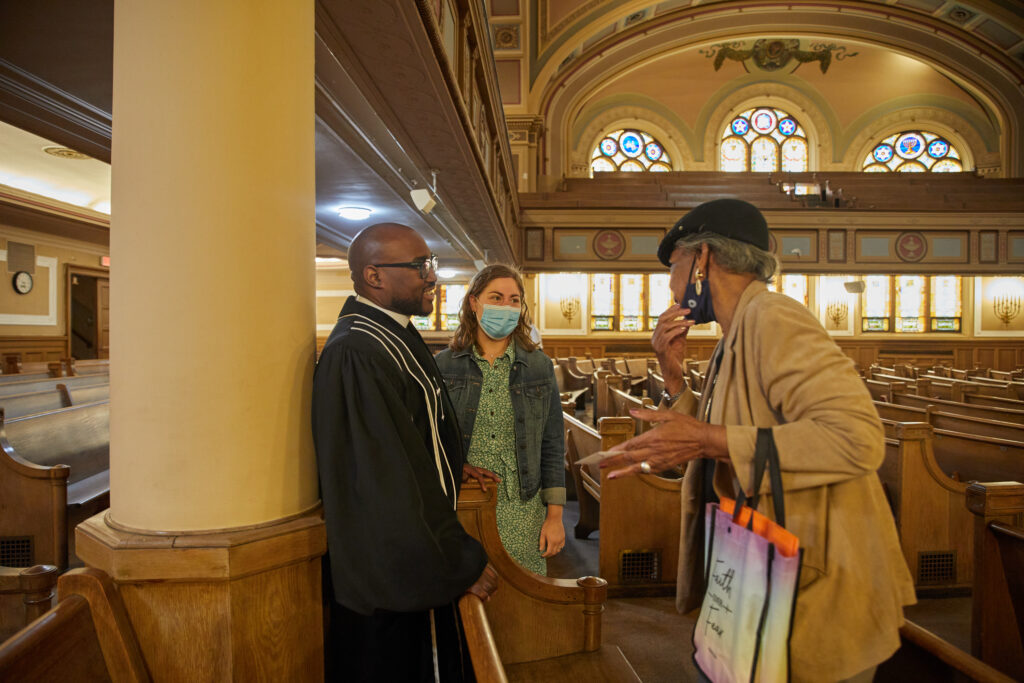

The Christian congregation that bought the Cleveland Jewish Center in 1946 remodeled the building but kept the Jewish iconography. There are menorahs on the walls of the sanctuary and a Star of David chandelier.

Kendrick smiles about it now. “I often joke and say Cory moved here and just put up a cross and went right to work,” Kendrick said.

There was a lot of work to do.

In the 1950s, the church had a membership of more than 3,000, according to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. More than a church, it was a bustling center of community life, much as it had been when it housed a synagogue—packing in guests for not just Sunday sermons but also community dances, festivals and more.

The church continued to operate the gym and swimming pool that came with the building. In 1961, the city of Cleveland rented the part of the building containing the pool and gym and declared it an official city recreation center. It remains so to this day.

Charles Williams, who has been a Cory church trustee since 1979, said the recreation opportunities were a lifeline for him when he moved to Cleveland with his family as a teenager in the 1950s. It gave him a place to belong when he didn’t know many people.

“Man,” said Williams, 84, “it was like a second home to me.”

It wasn’t the only lifeline that Cory extended to its neighbors.

The church established a credit union in 1958, at a time when getting loans was especially difficult for African Americans. (It operated until 2016, when it merged with another credit union.) Cory also organized youth sports leagues, offered dance and music lessons, formed its own community library and housed a day-care center.

But Cory’s most significant legacy involves opening its doors to civil rights organizers and activists. In addition to the high-profile speakers it attracted, Cory was a regular meeting place for rallies, discussions, voter registration drives and strategy sessions. In the 1960s, one of its pastors, Rev. Sumpter Riley, served as president of the United Freedom Movement, a union of 34 organizations, including the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality and many other groups that battled school segregation, discriminatory hiring practices and police brutality in Cleveland.

Many of the African Americans who came to Cleveland during the two Great Migrations—when Black people migrated from the South to the North after each world war—hailed from Alabama. So in 1963, when Bull Connor, the notorious Birmingham, Alabama, safety commissioner, unleashed his police dogs and fire hoses on African-American civil rights demonstrators—many of them children—the pain cut deep in Cleveland.

“It was not uncommon to refer to Cleveland as ‘Alabama North,’ ” said Ohio author James Robenalt in his book Ballots and Bullets: Black Power Politics and Urban Guerrilla Warfare in 1968 Cleveland.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was locked behind bars for leading those demonstrations. While sitting in his cell, he wrote his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail, which contains one of his most-quoted lines. “Injustice anywhere,” he wrote, “is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“We will meet physical force with soul force.”

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in a 1963 speech at Cory

Emmitt Theophilus Caviness, who has been senior pastor at Cory’s neighbor, Greater Abyssinia Baptist Church, since 1960, knew Martin Luther King Jr. well. He said King told him many times how fondly he regarded Cleveland. “King was very much at home here,” said Caviness, 95.

The news that King, fresh from that Birmingham jail, would be coming to Cleveland on May 14,1963 to speak at Cory was met with great excitement. “Thousands began lining up outside Cory Methodist Church early in the day, though King was not scheduled to speak until 7:30 p.m.,” Robenalt wrote, “and traffic backed up for miles around the church.” The crowd around Cory became so congested that King postponed his 7:30 p.m. speech until 8:45 so that he could make appearances at three other Black churches in the neighborhood to accommodate all who wanted to hear him. When he finally arrived to speak at Cory, the sanctuary was packed with 4,000 people, and another 5,000 listened outside through speakers.

“King was very much at home here.”

Emmitt Theophilus Caviness, senior pastor at Greater Abyssinia Baptist Church, Cory’s neighbor

“The walls were bulging,” reported the Call and Post, Cleveland’s Black-owned newspaper.

King called it the most enthusiastic welcome he’d ever seen.

In his Cory speech, King reiterated his determination to pursue justice through nonviolent protest. “We will meet physical force with soul force,” he said. “I am committed to nonviolence as a way of life.”

He called segregation a cancer.

“There comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression,” he said. “A time when people get tired of being pushed out of the glittering sunlight of life’s July and left standing in the chill November of an alpine winter.”

The Call and Post said King was repeatedly interrupted by thunderous applause. The baskets that were passed around the pews to collect bail money for jailed protesters in Birmingham raised $12,000, according to one account. “One group, unable to pass their contribution to Birmingham down from the crowded balcony, wrapped it in a silk scarf and tossed it down,” the newspaper reported.

A young girl, touched by the idea of kids facing the brutality of Bull Connor, donated the $50 her parents had gifted for her 12th birthday.

“I’m giving this money,” she said, “to the children of Birmingham.”

As a college student, Kendrick had several potential career paths in mind: politics, community advocacy, business entrepreneur, higher education. He always knew he wanted to be engaged in ministry, but he thought he’d do it as “the world’s greatest tither”—a lay person with a healthy bank account who could financially support the work of a church. After growing up in an impoverished neighborhood, he joked, making money might be nice.

But as a rising senior at Denison, Kendrick, who had been active in a campus ministry called Agape, saw a need.

The campus chaplain was expecting twins with his wife. The additions would give the family four children under 4. The balancing act, the chaplain knew, could be tenuous.

“Hey, why don’t I help you out?” Kendrick suggested. “I could be like a student chaplain.”

Kendrick spent his senior year helping lead chapel services and organize activities.

“I realized maybe there might be something in ministry,” he said, “that could be more a part of my daily life.”

“I realized maybe there might be something in ministry that could be more a part of my daily life.”

Rev. Gregory Kendrick Jr., Cory pastor

Ballots or Bullets

In the months between King’s May 1963 speech at Cory and Malcolm X’s April 1964 speech there, much happened. Civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated in June 1963 in Mississippi. The March on Washington in August 1963 attracted 250,000 people and culminated in King’s I Have a Dream speech. A month later, four African-American girls were killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

The alternating cycles of peaceful protests and violent backlash raised doubts about King’s tactics of nonviolent resistance. Among his most vocal doubters, few stood out like Malcolm X.

“Whereas Dr. King was a Christian, committed to nonviolence and in favor of integration, Malcolm X was a Muslim, committed to armed self-defense, and a separatist who espoused Black nationalism and a separate state,” Robenalt wrote.

Malcolm, who had joined the Nation of Islam (Black Muslims) in the 1950s, had a fiery personality that made him a celebrity in the early 1960s with frequent TV appearances. His rising profile led to tensions with his mentor, Elijah Muhammad. Muhammad was founder of the Nation of Islam who preached total separation of the races and a ban on participating in politics or even voting.

Just as his fame was reaching its zenith, Malcolm came to Cleveland to support a heated campaign against de facto segregation of Cleveland’s public schools. Black students in Cleveland attended schools in their neighborhoods, which were almost entirely Black because of redlining, deed restrictions and other discriminatory practices that restricted where Blacks could live. Although a separatist, Malcolm had lately grown more willing to participate in such integration battles as he distanced himself from Elijah Muhammad.

Leonard N. Moore, a professor of history at Louisiana State University who wrote a 2002 article on the Cleveland school struggle in the Journal of Urban History, summed up the grievances Black parents cited in complaining about the educations their children were receiving: “Inferior teachers, teacher segregation, a lack of remedial teachers, low teacher expectations, few Blacks in administrative positions, high student-teacher ratio, poor physical plant, inadequate social services and a severe lack of vocational courses. In comparison, schools on the all-white West Side had the most experienced teachers, the best services, the most attractive buildings and a low student-teacher ratio.”

School officials responded to the protests by planning to bus Black children to white neighborhoods, which had surplus classroom space. But the officials assured white parents that there would be no sharing of facilities: The Black students would be strictly segregated, with Black teachers brought in to instruct them.

The arrangement infuriated Black parents. They responded with demonstrations, marches, picketing and sit-ins, finally leading the school board in fall 1963 to promise true integration by the next year. But the board was in fact planning to build new schools in Glenville, which would return students to segregated classrooms.

Protesters were further inflamed when Ralph McAllister, the white school board president, publicly declared that African-American children were “educationally inferior” to white students.

A protest at Murray Hill School in the white neighborhood known as Little Italy had barely gotten underway on January 30, 1964, when violence erupted. Gangs of young white men beat several African Americans; threw rocks, bricks and bottles; and even attacked some police officers and news reporters. Leaders of the United Freedom Movement, which had been coordinating the civil rights demonstrations, abruptly halted the protest to avoid further violence.

It was into this tense atmosphere that Malcolm X, at the invitation of the Congress of Racial Equality, arrived at Cory to speak on April 3, 1964.

“During the 1950s and ’60s it was the site for civil rights activities.”

Margaret Lann, Cleveland Restoration Society

An estimated 3,000 people showed up at the church that night. The evening was billed as a debate between the radical Malcolm and the more mainstream activist Louis Lomax, an African-American writer who had co-produced a documentary on the Nation of Islam.

It was not a back-and-forth discussion. Lomax spoke first, followed by Malcolm X, who launched into a blistering indictment of American society.

“The question tonight, as I understand it, is ‘Where Do We Go From Here?’ ” he began. “In my humble little way of understanding it, it points toward either the ballot or the bullet.”

He predicted that 1964, a presidential election year, would be “the most explosive year” in American history. “Why? It’s also a political year,” he said. “It’s the year when all of the white politicians will be back in the so-called Negro community jiving you and me for some votes. The year when all of the white political crooks will be right back in your and my community with their false promises.”

He then reviewed how neither political party had delivered anything remotely resembling equal rights to African Americans, including the right to vote in Southern states.

“Let them know your eyes are open,” he said. “It’s got to be the ballot or the bullet. The ballot or the bullet. If you’re afraid to use an expression like that, you should get on out of the country; you should get back in the cotton patch; you should get back in the alley. They get all the Negro vote, and after they get it, the Negro gets nothing in return.”

Malcolm claimed he wasn’t advocating violence, just self-defense.

“It’s got to be the ballot or the bullet.”

Malcom X in a 1964 speech at Cory

“I’m nonviolent with those who are nonviolent with me. But when you drop that violence on me, then you’ve made me go insane, and I’m not responsible for what I do. And that’s the way every Negro should get.”

He told audience members that, yes, he’d work with them on school boycotts. “We will work with anybody, anywhere, at any time, who is genuinely interested in tackling the problem head-on, nonviolently as long as the enemy is nonviolent, but violent when the enemy gets violent.”

The Call and Post said most of the 3,000 listeners at Cory were “brought to their feet” by the speech. Malcolm X would repeat the speech 10 days later in Detroit.

The school protests that brought Malcolm X to Cleveland in early April 1964 continued after he left. On April 20 that year, Cory opened its doors to some of the 60,000 students, most of them Black, who participated in a citywide school boycott despite threats from school officials to take harsh action against them.

Cory Pastor Sumpter Riley hoped his church had made a statement. “Let no one go home and say that churches are remaining silent or inactive,” he said, “for we are doing our part.”

Less than a year later, Malcolm X, while preparing to speak in New York City, was shot multiple times and killed. Three men, all members of the Nation of Islam, were convicted in the killing. But the convictions of two of them were reversed years later, and mystery continues to surround the crime.

King, who would return to Cleveland many times, was assassinated in 1968 in Memphis, where he had traveled to support a strike by city sanitation workers. James Earl Ray pleaded guilty to King’s murder in 1969, but King’s family has long maintained the crime actually sprang from a high-level conspiracy and that Ray was a scapegoat.

As for school integration in Cleveland, it would be late 1979 before court-ordered busing would achieve it.

After graduating from Denison, Kendrick took a job in multicultural recruitment at Ohio Northern University and then entered the Methodist Theological School in Ohio (MTSO).

He expected to graduate as a Baptist pastor. But a stint as a student minister at Broad Street United Methodist in Columbus changed his heart.

John Wesley, founder of Methodism, once wrote: “The gospel of Christ knows of no religion, but social; no holiness but social holiness. Faith working by love, is the length and breadth and depth and height of Christian perfection.”

Kendrick found the emphasis on community captivating.

The husband and father of two began serving Methodist churches in Columbus and Cleveland.

‘I Need to Stay’

Kendrick is somewhat soft-spoken for a preacher. It’s hard to imagine any hellfire and brimstone coming from his pulpit. He’s warm but maintains a certain reserve—especially for making anything, including conversation, about himself. There is, however, a quiet firmness, a directness and a thoughtfulness to the way he expresses himself that leaves little doubt about his convictions.

Kendrick arrived at Cory in late 2019, on what was supposed to be a temporary assignment. “The goal,” he said, “was that I would be here for 3 months to try to figure some things out.”

He began hearing talk of two major challenges: First, the massive building—95,000 square feet—needed too much repair. Second, the small congregation—it averages perhaps 40 worshippers on a typical Sunday—was dwindling too quickly to justify keeping the building open.

The building, Kendrick acknowledges, needed—and still needs—work. “There would be weeks on end when I would come in,” he said, “and my main job was to see what was leaking today.”

Then, in early 2020, the coronavirus pandemic hit.

But Kendrick felt called to counter pessimism about the church’s future. The biblical prophet Nehemiah, he said, was his inspiration. When Nehemiah hears of the desolation and poor conditions of his people, he weeps—and then prays to God that he may have the blessing and strength to work for the collective good of his people. “When I saw what people were experiencing and how greatly they were being affected in the early pandemic,” Kendrick said, “I had a similar prayer to God.”

Kendrick went to his bishop.

“I need to stay,” he said.

Kendrick immediately faced COVID-induced, gut-wrenching choices.

Cory had provided the neighborhood with food for 50 years through hot meals and a free pantry. But some of the food was unhealthy or low-quality. Other food came from agencies requiring Cory to collect income information from recipients, a practice Kendrick disliked. And keeping up with growing demand was pushing volunteers to a physical breaking point. After wrestling with the decision for months, Kendrick closed the pantry and stopped serving hot meals. “There was disappointment, shock,” Kendrick said. “People still ask when we will open again.”

But the church’s goal, he noted, was never was to be a grocer. “The vision,” he said, “was always a sovereign and sustainable community that had everything it needed within it to be successful.” Kendrick is planning to realize that vision by partnering with local farmers to supply fresh food that will be distributed to neighbors in need. “It’s more sustainable,” he said. “It allows us to make connections with folks who are local. It allows us to provide more nutritious food.”

Then, 2021 brought a bright spot: Cory became the first site designated as a spot on the Cleveland African-American Civil Rights Trail—a project funded in part by Ohio Humanities that denotes locations important to the civil rights movement.

“Churches aren’t just religious institutions, they’re also places where people find fellowship, leadership.

Aaron Fountain, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Cory has also attracted more than attention for its significant history: It’s attracted grants that have kept it at least temporarily afloat. Among its gifts: About $1M from the National Park Service for building preservation, $150,000 from the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund for the same purpose and $25,000 from the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District for a green infrastructure project to install permeable pavers in its parking lot and harvest rainwater from its roof.

Kendrick’s vision for continued survival is to take advantage of the building’s size and amenities—it has two commercial kitchens and much empty space—to create opportunity for neighborhood residents.

Can it be an entrepreneur incubator? he wonders.

Can Cory offer a commercial kitchen where an aspiring restaurateur who is working on some recipes in their home can level up?

Can it be a place where an aspiring saxophonist can come to practice and even host a recital?

“We have these spaces,” Kendrick said. “How do we create the vehicle where those things can happen?”

Kendrick knows exactly why he stayed: the Cory stories. There were so many stories, he said. And there could be so many more.

People shared tales of how Cory affected them—how they learned to swim at Cory, or ski through Cory, or meet with the Boy Scouts inside Cory. They echoed some of Kendrick’s own experiences growing up with a church just down the street as a place of comfort, refuge and inspiration.

“When people began to tell me their own narratives of joy, of helpfulness, I realized, ‘Oh there’s something here,’ ” he said. “It was people telling me this place is worth cherishing and that this place still has value to offer to the world.”

The Resurrection

As Cory eyes its future, it is looking to lock arms with the congregation that preceded it.

The two congregations—one Jewish, one Christian—that have worshipped at 1117 E. 105th Street have forged new ties in recent years.

The Jewish congregation that built Cory is now known as Park Synagogue and is located in the Cleveland suburb of Pepper Pike. In 2016, it received a grant to locate two Little Free Libraries—the tiny, house-shaped book cases that have popped up in many cities—wherever it chose. Park chose to put them both at Cory.

The synagogue had no ongoing relationship with the church back then, said Ellen Petler, Park’s program and volunteer director. Given their historic connection, she thought it was time they developed one.

The library project was well-received by both congregations and led to regular events between the two. There have been joint choir concerts, Martin Luther King Jr. Day observances, a Passover seder recognizing the enslavement suffered by both the Hebrews of the Bible and the Africans brought to America in chains, and conversations about the twin evils of racism and anti-Semitism.

Petler told a TV interviewer in 2022 that she found the Seder particularly poignant.

“It was a beautiful event that helped people from both congregations see that being free is something we shouldn’t take for granted,” she said. “That both of our peoples came from a history of slavery to freedom and we have to continue to work every day to make sure all people are free.”

There are no lack of voices expressing respect and affection for Cory, the contributions it has made in the fight for racial justice and the way it has cared for its neighbors in Glenville. The grants it has attracted and the honors it has received speak to the importance of ensuring its survival, said Lann of the Cleveland Restoration Society.

Losing it would leave both a literal and a spiritual hole in the neighborhood, said Aaron Fountain, who worked as a researcher on the Civil Rights Trail project and is now web content editor for the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C.

“You (would) lose a sense of community,” Fountain said. “Churches aren’t just religious institutions, they’re also places where people find fellowship, leadership.”

Case Western Reserve University Professor John Grabowski, a respected scholar of Cleveland history, said that in many ways, places provide tangible evidence of the past that can evoke individual and community memory. And in an increasingly virtual world, he noted, losing places like Cory would create a void.

“It is not only the site of major events in the history of Cleveland’s African-American community, it is also a site with deep religion connections, both to the Jewish and Christian community,” Grabowski said. “It has hosted weddings, wakes, bar mitzvahs and the religious services which underpin and outline the cycle of human life. The tangible is increasingly important in a world consumed by and, to some extent, ruled by the virtual. To lose a structure such as this would create a vast void in personal and communal memory.”

“To lose a structure such as this would create a vast void in personal and communal memory.”

John Grabowski, Cleveland scholar

Charles Williams, the long-serving Cory church trustee, was in the midst of remodeling a church bathroom with another volunteer when asked his opinion about Cory’s future.

“I got this hope in my heart and mind that at some point we will have some young people that will come back and will want to do something good in Cory and in Glenville. I think if Glenville thrives, Cory will thrive,” he said. “I still feel that if you do all that you can, then God will take care of the rest. And that’s why I’m in that bathroom right now, trying to make it look nice.”

Methodist officials recently took another step toward ensuring that Cory will continue to be a beacon in Glenville. The church is teaming up with St. Matthew United Methodist in the neighboring Hough community of Cleveland to share resources—including some funding.

“I got this hope in my heart and mind that at some point we will have some young people that will come back and will want to do something good in Cory.

Charles Williams, Cory church trustee

“It is another predominantly Black congregation that was actually birthed out of Cory in the late 1940s,” Kendrick said. “The goal is to create a cooperative between the two to share resources that allow each to continue to be deeply rooted and committed to their respective neighborhoods.”

Kendrick said he agrees with Williams that Cory’s future is tied to Glenville’s future. But, like the civil rights leaders who saw the obstacles ahead and kept moving forward anyway, he is determined to carry on.

He knows there are questions about the church’s survival.

But for him, it’s a matter of faith.

“I’m not naïve or Pollyanna. I know the lifecycles of churches,” Kendrick said. “I am, however, a person of resurrection. That’s what we believe. Whether literal or symbolically, we believe that resurrection is possible.”

Behind the Story

Meet the creatives behind the story on Cory United Methodist Church.

JOE BLUNDO

Joe Blundo is one of Ohio’s longest-tenured award-winning journalists. He is a master observer and thoughtful reporter who has written for The Columbus Dispatch for over 40 years. He’s spent most of those years as a columnist with a distinctive voice who covers topics from the hilarious to the poignant. Here, he shares a few thoughts on The Story of Cory.

You said you will carry two things with you from this story. What’s the first?

First, I keep thinking about all those people jammed into Cory, not just for those two iconic speeches but for all the rallies and voter registration drives and protest meetings and food distributions and dance classes. Would any of that have happened if it wasn’t for the presence of churches? I know we live in an increasingly secular society, and certainly Christianity has a lot to answer for. But I’m not sure what would replace churches as engines of social cohesion if they ever cease to exist.

And the second?

Second, I realize how much I still don’t know about the civil rights movement that I thought I knew all about. It hadn’t dawned on me until I researched this story that a connection would exist between Alabama and Cleveland and that the brutality practiced in Birmingham in 1963 would stir deep emotions among Clevelanders who used to live there.

Favorite gem?

As someone who does a lot of volunteer work involving tools, I completely identify with Cory church trustee Charles Williams when he basically says he expresses his affection for his church by remodeling its bathroom. We all have our love languages.

DE’SHAUNAE MARISA

De’Shaunae Marisa is a Cleveland native who grew up attending church on the city’s east side. Now, she is an accomplished photographer and teaching artist who lives in Los Angeles and uses her work to spread stories of power and upliftment to communities of color. Her goal, she says, is to represent authenticity with compassion. Her work has been featured in publications worldwide, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone and National Geographic, and her client list includes companies like Nike, Converse, Hollister and Target. Here, she reflects on capturing photos for the Cory story.

What intrigued you about this story?

I am greatly intrigued by the idea that two separate religious communities could occupy a space so beautiful in architecture and large in size. It fascinates me to see a Black community revive a space that was left by the previous owners and not change much of the interior. I was also interested in the major decline of the church community. Seeing the few members in the rows of pews in contrast to the 60s was such a shock but very accurate to how people are feeling about religion.

What do you hope you captured with your photos?

I hope I captured the feelings of loss among the vast community but also the love that the remaining community shares for one another.

What will you carry with you from this?

I will carry the feeling of wonder stepping into the church and seeing it for the first time. I will remember the wonderful conversations I had with the church members and connecting with Rev. Kendrick. I appreciate the work he is doing in the community and to keep the congregation uplifted.